[ad_1]

With the sentience of vertebrates now enshrined in UK and EU law, is it time we rethought our relationship with fish?

If you’ve ever had a pet, visited a zoo or watched wild animals at play, it’s likely you’ve considered the concept of animal sentience.

Loosely defined as the ability to experience both positive and negative emotions, such as pleasure, joy, pain and fear, animal sentience acknowledges that living creatures have feelings and awareness.

The complexity of these emotions depends on the species, but many countries – including the EU bloc – have laws in place recognising the sentience of certain animals.

While acknowledging sentience might seem like a small step, it can have profound ethical and philosophical implications for the way that we treat wild, domesticated and farmed animals.

Though scientists have long agreed that certain species – such as primates and other mammals – are sentient, the sentience of other groups, including fish and decapod crustaceans (a family that includes crabs, lobsters and shrimps) has been debated for decades.

But with the sentience of all vertebrates (animals with backbones) now enshrined in UK and EU law, is it time we rethought our relationship with fish and other farmed animals?

At Compassion in World Farming’s recent London conference ‘Extinction or Regeneration: Transforming Food Systems for Human, Animal and Planetary Health’, scientists and policymakers met to discuss the role that sentience plays in our treatment of farmed animals.

What do we mean when we talk about animal sentience?

The exact definition of sentience varies from country to country, with some states refusing to define the concept at all. This highlights the difficulty in pinning down what it means to feel. While different species experience the world in different ways, depending on the complexity of their brains, humans also suffer from a lack of imagination when it comes to interpreting animal emotion.

Our inability to interpret it doesn’t mean an animal isn’t experiencing the world emotionally though, as João Saraiva, leader of the Fish Ethology and Welfare Group and president and founder of the FishEthoGroup Association told Euronews Green before the conference.

“The problem with fish is that they are very distant from us. It’s very hard to incorporate fish into what we call the circle of empathy. We cannot empathise with fish in the same way we empathise with a cow or with a dog,” explains João.

“Fish don’t have facial expressions, they don’t blink, they don’t smile. And we rely on these cues as humans to create empathy.”

It is this empathy gap, rather than a lack of scientific data, that has kept myths such as ‘fish can’t feel pain’ and ‘goldfish only have three-second memories’ in the public consciousness for so long.

Thankfully though, as a packed room for the ‘Soils, seas and sentient beings’ panel showed, attitudes to animal sentience are beginning to shift.

Animal sentience and the law

The 17th century French philosopher René Descartes believed that all animals were automatons, without feeling or consciousness. This philosophy set the tone for centuries to come, with animal suffering widely dismissed across the board.

By the 20th century though, views were beginning to change, and in 1965, John Webster, a founding member of the UK Farm Animal Welfare Council helped to enshrine the ‘five freedoms’ of animals into UK law.

“Animal welfare was just a fuzzy subject at the time, an emotional subject without rules,” he tells Euronews Green. “We tried to develop rules for animal welfare, and now in recent years I’ve been trying to structure thinking in regard to animal sentience and sentient minds.”

The five freedoms – including the freedom from discomfort and pain – have since been adopted by welfare groups around the world, including the RSPCA and the World Organisation for Animal Health.

Though these freedoms acknowledged the potential suffering of animals, they did not explicitly acknowledge their inner emotional worlds. But as scientific research into animal sentience continued, governments began to recognise it in law.

Article 13 of the Lisbon Treaty, which came into force in December 2009, states that in the formulation of policies, “the [European] Union and member states shall, since animals are sentient beings, pay full regard to the welfare requirements of animals”.

Despite this though, many farmed animals are still seen as products rather than sentient individuals, and nowhere is this more apparent than in fish farming.

Do fish feel pain?

“So there was a policy being proposed in Germany [in the 1980s] to ban angling catch and release,” says Jennifer Jacquet, Associate Professor in the Department of Environmental Studies and Director of XE: Experimental Humanities and Social Engagement at NYU.

“And the history of the fish pain debate shows that the idea of fish not feeling pain comes directly out of the threat of that policy.”

While the theory that fish can’t feel has been in the public consciousness for decades, João is keen to point out that it’s not true.

“It has been demonstrated many, many times that the fish brain, even though it is different, has the same functions [as the human brain]. You can actually build a functional map of the fish brain and surprise, surprise, there is a functional area that makes animals feel pain,” he explains.

More recent research, João continues, has shown that fish have the same nociceptors as we do too. Nociceptors are part of the sensory nervous system found in skin and tissues, which transmit pain signals to our brain.

Is aquaculture ethical in its current form?

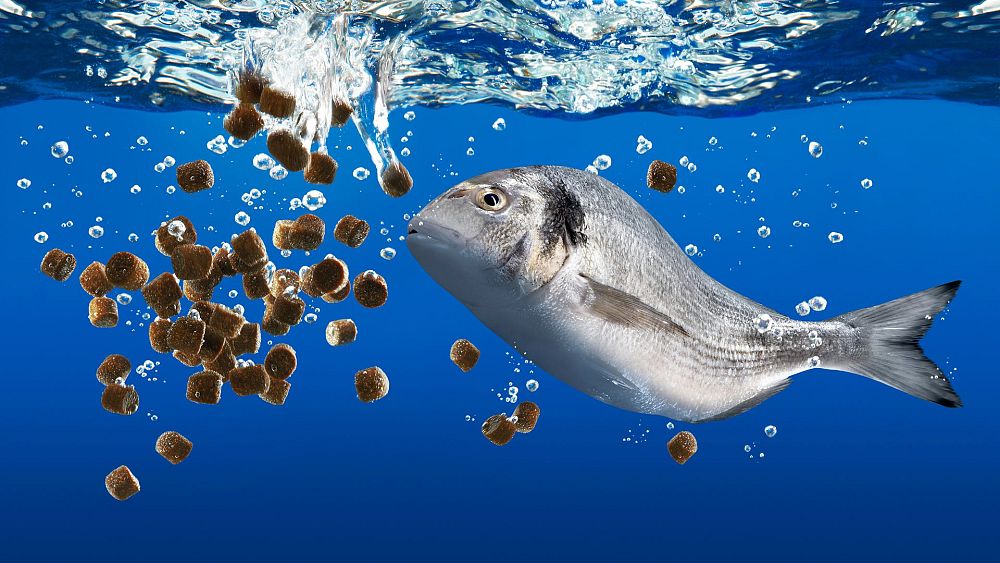

Fish farming, also known as aquaculture, is a rapidly expanding market globally. Bred, raised and harvested in controlled environments, millions of tons of wild fish are killed every year in order to feed farmed fish.

According to Jennifer, around 20 per cent of all wild fish killed by humans are turned into fishmeal and fish oil. These products are then fed to factory farmed animals or sold as supplements for human health.

So while fisheries are often touted as the answer to global hunger, says Jennifer, they are actually extremely inefficient.

“This is really about taking fish from the global south and turning it into fishmeal, to feed farmed fish as well as other farmed animals,” she explains.

“When we talk about these food systems, people want to say ‘The human population is growing, we’re going to be 12 billion’ but when you drill down and ask ‘Well, how many of our crops are currently going to animal feed? How many of our fish are going to other farmed animals?’ When we look at these giant inefficiencies the argument isn’t even there.”

Added to this, Jennifer explains, aquaculture is expanding so rapidly, species are being farmed before any welfare data is available to allow them to be farmed ethically or responsibly.

“We analysed the 408 species that are currently under aquaculture production and showed that less than a quarter of these have any specialised welfare knowledge… So 70 per cent of all individual animals in aquaculture have little to no welfare or knowledge.”

Without the relevant welfare information, it is impossible to respect the sentience of fish species and farm them in an ethical way. One species that Jennifer is sure animal welfare experts know enough about though, is octopuses.

“We believe that for octopus farming, we actually know enough about octopuses to know that we will not give them a good life in captivity.”

Octopus farming – a step too far?

João agrees. “It’s very difficult for the octopus to experience good welfare in any farming conditions.

“Octopuses are solitary animals. They’re carnivorous, they’re aggressive, they make use of their surroundings, so tanks would not be in the best interest of the octopus.”

The skin of an octopus is an incredible multi sensory organ too, allowing the octopus to see, feel, taste and touch. If this skin is damaged in a fight, the octopus will be unable to recognise its own arm, and believing it is a foreign object, will attack itself.

Injuries like these are more likely if these naturally solitary animals are kept in close confinement. With Nueva Pescanova, the world’s first octopus farm, currently in the planning stage in the Canary Islands, there is growing concern that these highly intelligent animals will be exposed to high levels of suffering.

“It’s not even food production, it’s a luxury good,” says Jennifer.

“I really wish both the money, you know, the initial spending and certainly the question of whether it should go forward was up for a democratic vote. I actually have a lot of faith that people don’t think this is the best way forward.

“This is really about capital and power working in a way that goes against our basic instincts about what is right and wrong.”

Is lab-grown meat the answer?

While for some, going meat-free is the only adequate response to the idea of animal sentience, many people globally rely on animals as their main source of protein or their livelihood, as Jennifer acknowledges.

“In general, I think we should consider abolishing industrial fisheries and [favour] artisanal, small-scale and subsistence fisheries, which feed more people directly.”

While many people aren’t reliant on fish as a source of protein, seafood is still highly desired globally, with demand particularly high in wealthy Western nations.

Without aquaculture, how can this demand be met without putting more pressure on wild fish populations?

“I think there’s a really interesting role for something like cellular seafood to emerge in the marketplace as an option for wealthy Western consumers,” says Jennifer.

“We can fill the void with this cellular product that is pain free, slaughter free and ecologically much less damaging.”

While cultured meat is being produced on a very small scale, the current costs – both environmental and financial – mean the industry is unlikely to scale up anytime soon.

For the foreseeable future then, if we want to eat animal protein, we will have to continue to battle with the ethical implications of killing farmed and wild sentient animals.

[ad_2]