[ad_1]

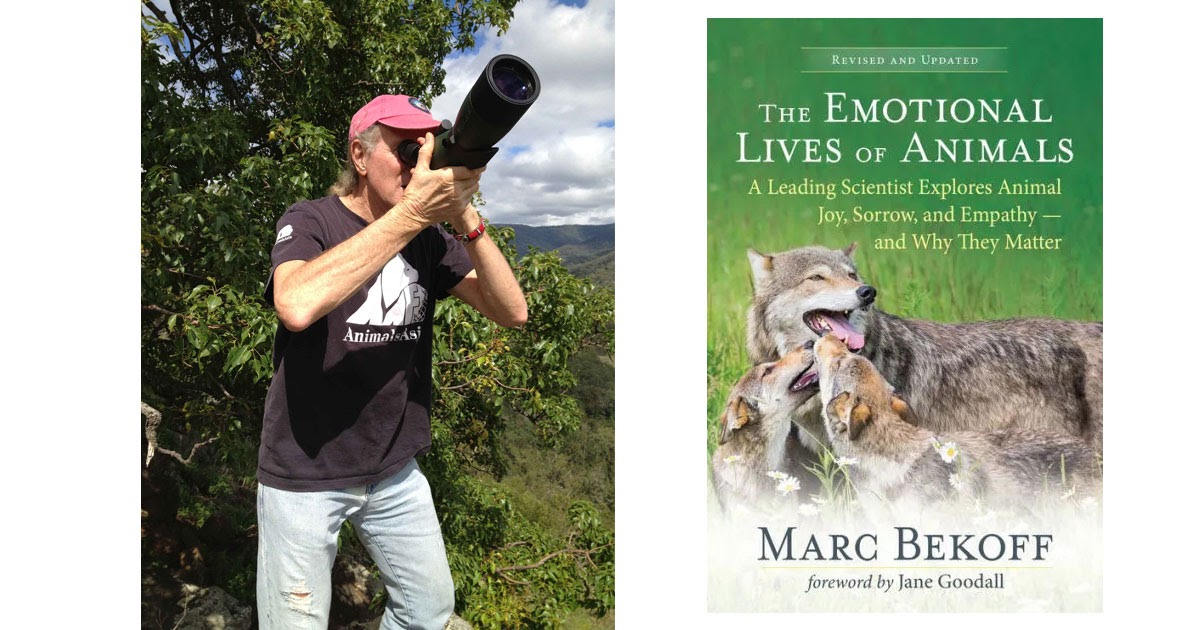

An excerpt from Marc Bekoff PhD’s new, revised, edition of The Emotional Lives of Animals: A Leading Scientist Explores Animal Joy, Sorrow, and Empathy–and Why They Matter.

By Marc Bekoff, PhD

University of Colorado, Boulder

***Don’t miss the chance to hear Marc Bekoff PhD speak at Bark! Fest, the book festival for animal lovers. He’s part of a panel on Canine Emotions and Perception with Zazie Todd PhD and Cat Warren on Tues Sep 17, and he’s presenting about Animal Emotions on Mon Sep 23***

“Anthropocentrism is at the root of all abuse of our fellow creatures on earth — the logically unsupportable belief that humans are the only species on the planet worthy of consideration.”

— Sir Brian May, founding member of Queen and Save Me Trust

A person would have to be totally out of touch not to know that nonhuman animals (animals) are being wantonly and brutally slaughtered globally in a wide variety of anthropocentric (human-centered) activities. The Anthropocene, often called “the age of humanity” has morphed into “the rage of inhumanity.” To be able to maintain some degree of hope for the future, it’s important to pay close attention to our successes on behalf of nonhuman animals, since it’s far too easy to focus on the challenges and the harm that is still being done. Of course, animals need our help more than ever, but many good things are happening. Compassion fatigue and empathy fatigue can take their toll if we forget to appreciate progress and take care of ourselves.

Perhaps the most important thing is that caring for other animals is increasingly becoming a mainstream concern for a growing number of humans. It is no longer radical to recognize, respect, and want to protect the emotional lives of animals. Further, people increasingly see how we ourselves benefit by acting with more empathy, kindness, respect, and compassion for all the world’s creatures. It can be true that other animals often suffer in silence, since they can’t speak to us directly, but more and more people are learning how to read their behavior and speak for them.

This page contains affiliate links which means I may earn a commission on qualifying purchases at no cost to you.

While it is by no means a universal sentiment, I find that people are expressing more humility toward other animals and nature, perhaps as a consequence of the unmistakable damage our presence has caused. David Attenborough rightly notes, “I think sometimes we need to take a step back and just remember we have no greater right to be here than any other animal.” He also notes, “Sometimes we might remember that all other animals have every bit as much right to be here and to be unmolested as any human does.”

All the research and studies of the last twenty years are helping us to recognize that caring for the well-being of nonhuman animals is the right thing to do. Caring crosses species borders. Good examples are the One Health and One Welfare initiatives, which are driven by the premise that caring for and working on behalf of other animals also helps us and is a way to care for ourselves. This caring allows people to rid themselves of the cognitive dissonance they experience over all the various types of harm that people cause to animals. Animal emotions are a matter of importance in their own right, but the very presence of animals — with their free-flowing emotions and empathy — is also critical to human well-being. As Denver University’s Dr. Sarah Bexell aptly puts it, “The One Health approach is a way of looking at the world that helps humans to see and acknowledge that humans, other species, and the natural environment are completely interlinked. If we harm one of these three pillars, all three are harmed.” Similarly, wolf expert John Vucetich and his colleagues note, “Caring for nonhumans, for their own sake, does not preclude caring for humans. Humans are more than capable of caring for many more than one kind of thing…. Nothing is inherently misanthropic about being nonanthropocentric.”

If we continue to allow human interests to always trump the interests of other animals, we will never solve the numerous and complex problems we face. We need to learn as much as we can about the lives of wild animals. Our ethical obligations also require us to learn about the ways in which we influence animals’ lives when we study them in the wild and in captivity, and what effects captivity has on them. As we learn more about how we influence other animals, we will be able to adopt proactive, rather than reactive, strategies. We should honor the rights of individuals to be free to live the lives they’re meant to live — to be free to perform species-typical behaviors whether we like them or not. There’s a certain wholeness when a wolf, coyote, eagle, robin, trout, or snake is allowed to be who they’re supposed to be.

“Emotions are the gifts of our ancestors. We have them and so do other animals.”

The fragility of the natural order requires that people work harmoniously so as not to destroy nature’s wholeness, goodness, and generosity. The separation of “us” (humans) from “them” (other animals) engenders a false dichotomy. This results in a distancing that erodes, rather than enriches, the numerous possible relationships that can develop among all animal life. What befalls animals befalls us. A close relationship with nature is critical to our own well-being and spiritual growth. And independent of our own needs, we owe it to animals to show the utmost unwavering respect and concern for their well-being.

I find the word solastalgia, which was coined by Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, to be appropriate here. It describes “the distress caused by the lived experience of the transformation of one’s home and sense of belonging and is experienced through the feeling of desolation about its change.” We experience solastalgia when we erode our relationships with other beings.

It’s easy to become anthropocentric and forget that humans are fellow animals. Our species is different, but it’s also the same. Theologian Stephen Scharper resolves this contradiction with his idea of an “anthro-harmonic” approach to the study of human-animal interrelationships. This view “acknowledges the importance of the human and makes the human fundamental but not focal.” We are all in the world together. We and other animals are consummate companions, and we complete one another. Theologian Thomas Berry expresses this same idea a little differently. He says each and every individual is part of a “communion of subjects,” in which our shared passions and sentience provide the foundation for a closely connected community. No one is an object or an other; we are all just us.

When we’re unsure about how we influence the lives of other animals, we should give them the benefit of the doubt and err on the side of the animals. It’s better to be safe than sorry. Many animals suffer in silence, and we don’t even realize this until we look into their eyes. Then we know.

Personal Choices, Personal Rewilding, and Actually Doing Something

What should we do with what we know? What sorts of choices should we make? We must use what we know on behalf of all animals. I will admit, I get cranky and irritable now and again. I’m tired of reading studies and essays about animal behavior, animal cognition, animal emotions, and animal sentience that trumpet new discoveries and then end by saying something like, “We need to treat other animals better — with more respect, compassion, kindness, and dignity.” Of course we do. These banal platitudes of pain don’t do anything for me — why does the US Federal Animal Welfare Act still write off lab rats and mice as not being animals, and why, as of 2022, can more pigs be killed per hour in slaughterhouses than previously allowed? We need a breakthrough paradigm shift in how we treat other animals and a call for heartfelt action on their behalf, one that leads to changes in our laws, regulations, and animal-human interactions.

We need to stop visiting and saying the same old same old to justify slaughtering sentience and causing widespread reprehensible pain to trillions of animals each and every year. The “animal kill clock” keeps tabs on the number of animals killed annually for food, and the number that shocks me the most is the number of animals killed since I last visited their page. One day, it estimated that more than 22,000 animals were killed for food in the United States every ten seconds. This simply is, as a 10-year old once said to me, “Disgusting, and you adults have to get your act together.”

While I was revising The Emotional Lives of Animals: A Leading Scientist Explores Animal Joy, Sorrow, and Empathy I came across a lot of new material as well as some old material that I hadn’t discovered before. All of it supports what I wrote in the first edition in 2007 and have been writing about ever since. The only thing that’s changed is that we’ve confirmed that more animals than we ever thought are emotional and aware, and so the biodiversity of sentience has only continued to expand. Now it’s time to use that knowledge to enforce existing welfare regulations and laws while also improving them, making them more stringent and with real consequences for violations, so people might think twice before choosing to harm and kill other animals. I hope this update inspires you to do something — anything, big or small — that improves the lives of nonhumans. Everyone can make a difference. That said, it’s essential to work for animals and not against people. Through respectful coexistence, we can find a way to our share our magnificent and fascinating planet.

From time-to-time I find myself thinking about the adage, “After all is said and done, a lot more is said than done.” And while we’re pondering and revisiting questions and ideas about animal sentience and emotions that should have been put to sleep decades ago, countless animals are tortured and killed. I hope what I’ve written inspires people to reduce the gap between saying and doing. Everything we have learned warrants this paradigm shift, and nothing we have learned calls for allowing continued or additional abuse. When we don’t use what we know, we let animals down, and as a result we let ourselves down — what harms them harms us, and what benefits animals makes life better for all.

What this means is that we each must make our own decisions and choices and take responsibility for our own actions. Individual responsibility is critical. The problems that animals face, and that we face in caring for them, can be overwhelming. It’s easy to become discouraged, it’s easy to feel lost and powerless, and it’s easy to put the blame on institutions and corporations, on “society,” and fail to address our own behavior.

How do I decide what to do? Simply put, I try to make kind choices — choices that are fair and just. I try to increase compassion and reduce cruelty. I also try to practice what I call the “13 P’s of rewilding”—being proactive, positive, persistent, patient, peaceful, practical, powerful, passionate, playful, present, principled, proud and polite. These were expanded from my book Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence.

And I try to make it simple and fun. When I talk with people about what they can do to help animals and our wounded planet, I always stress how easy it is to do something positive —people don’t have to found an organization or spend a lot of time doing what they decide to do. They can build small actions into their daily lives. I’m certainly far from perfect, but these goals motivate me daily. They guide me when I’m not sure what’s right. When I challenge people, usually scientists, by asking, “Would you do it to your dog?” I’m really just trying to remind them to act with compassion. I’m trying to shock them into remembering the golden rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Who could possibly argue that all beings aren’t deserving of the best lives possible?

To me, this includes personally rewilding our hearts from the inside out. We need to reconnect with other animals and with the magnificence of nature that forms their homes. We need to dissolve false boundaries to truly connect with both nature and ourselves, and one way to do this is to put aside our self-centered mindset. One of my favorite bumper stickers is “Nature bats last.” We can try to outrun and outsmart nature, but in the end, she always wins. Will we allow ourselves to become one of the species that didn’t make it? Or worse, will we continue to be the one species that threatens all others and who allows uncounted species and individuals to perish so we can live where and how we please? I hope not.

In practice, rewilding means walking through the world treating every living being like an equal — not the same, but as a being with an equal right to life. The golden rule applies to human animals, other animals, trees, plants, and even Earth itself. My colleague Jessica Pierce says that we need more “ruth,” a feeling of tender compassion for the suffering of others. Ruth is the opposite of ruthless, or being cruel and lacking mercy. I agree. Kindness and compassion must always be first and foremost in our interactions with animals and every other being in this world. We need to remember that giving is a wonderful way of receiving.

Living up to this simple pledge is not easy. Believe me, I know. To do so, we must overcome fear — fear of going against the grain, fear of coming out of the closet, fear of ridicule, fear of losing grant money or irritating colleagues, and fear of admitting what we’ve done or are doing to other sentient animals. Sometimes when we find it difficult to overcome our fears, a debilitating feeling of shame can paralyze us, but we must remember that every day brings new opportunities. No matter how small the gesture, anytime we act with compassion and do what we feel is right, despite the negative consequences (whether actual or imagined), we make a difference, and that difference matters.

In March 2006, I gave a lecture at the annual meeting of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees in Boston. I was received warmly and the discussion that followed my lecture was friendly, even though some in the audience were a bit skeptical of my unflinching stance that we know that certain animals feel pain and a wide spectrum of emotions. After my talk, a man came up to me who’s responsible for enforcing the Animal Welfare Act at a major university. He admitted that he’d been ambivalent about some of the research that’s permitted under the act, and after hearing my lecture, he was even more uncertain. He told me that he’d be stricter with enforcing the current legal standards, and he would work for more stringent regulations. I could tell from his eyes that he meant what he said, and he understood that the researchers under his watch would be less than enthusiastic about his decision. But he needed someone to confirm his intuition that research animals were suffering, that the Animal Welfare Act was not protecting them. I was touched and thanked him. Then he put his head down, mumbled, “Thank you,” and walked off.

One notion I’ve been writing a lot about lately is “rewilding education.” It meshes well with what humane educator Zoe Weil has said — the world becomes what we teach. One aspect of that is getting youngsters off their butts and out into nature. Also, we can encourage schools and parents to include humane education, so we raise children who both understand that animals have feelings and, more importantly, translate this into their daily lives and choices. Not only will our children benefit, but so, too, will future generations as we all negotiate the challenging and frustrating path through the Anthropocene.

I’m an optimist and really believe that with hard work, diligence, and courage we can right many of the wrongs that animals suffer at our hands. There are many wonderful people working in a myriad of ways, large and small, to make the lives of animals better. Some efforts are very public, and some are private, but together they help to realize a peaceable kingdom here on Earth, in which all beings are blanketed in a seamless tapestry of compassion and love. Surely, no one can argue that a world with more respect, compassion, and love would not be a better place in which to live and to raise all of our children. My message is a forward-looking one of hope. We must follow our dreams.

All I ask is that you reflect on how you can make the world a better place; chiefly, how you can contribute to making the lives of animals better. Do this when you’re alone, away from others, so that you can feel free to look deeply and assess your current habits and actions absent peer or any other sort of pressure. It’s always a sobering experience to try to view ourselves as we really are. In this case, ask yourself, how do your current actions affect other animals, and what can you do differently to care for animals better? Even when a situation is beyond my ability to change it, I make a point of apologizing to each and every individual animal who finds themselves being subjected to inhumane treatment. I believe that even just the expression of compassion can make a positive difference in the life of someone who is suffering. Silence is the enemy of social change.

We owe it to all individual animals to make every attempt to come to a greater understanding and appreciation for who they are in their world and in ours. We must make kind and humane choices. There’s nothing to fear and much to gain by being open to deep and reciprocal interactions with other animals. It’s not “radical” to care for and protect animals from horrific abuse each and every second of the say, it’s a matter of respect and decency and we need to get over the absolutely inane idea that we are “better,” “more valuable,” and “higher” than other animals. Biology and common sense clearly tell us that this this sort of anthropocentrism is one of the dumbest things a person can say.

Animals have in fact taught me a great deal: about responsibility, compassion, caring, forgiveness, and the value of deep friendship and love. Animals generously share their hearts with us, and I want to do the same. Animals respond to us because we are feeling and passionate beings, and we embrace them for the same reasons.

Emotions are the gifts of our ancestors. We have them and so do other animals. Emotions can reconnect us to the world at large and help us truly coexist with other animals. We’re all on this journey together and every single individual matters. When we help other animals, we also help ourselves. By allowing ourselves to emotionally connect with all life, we can make life better for everyone — a win-win for all. We must never forget this. And we need to get off of our rumps and do something now.

Excerpted and modified from: The Emotional Lives of Animals: A Leading Scientist Explores Animal Joy, Sorrow, and Empathy―and Why They Matter (April 2024).

About Marc Bekoff PhD

Marc

Bekoff is professor emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the

University of Colorado, Boulder, He has published 31 books (or 41,

depending on how you count multi-volume encyclopedias) and has won many

awards for his research on animal behavior, animal emotions (cognitive

ethology), compassionate conservation, and animal protection, has worked

closely with Jane Goodall as co-chair of the ethics committee of the

Jane Goodall Institute, and is a former Guggenheim Fellow. He also works

closely with inmates at the Boulder County Jail.

In June 2022, Marc was recognized as a Hero by the Academy of Dog Trainers. His recent books include Canine Confidential: Why Dogs Do What They Do, Unleashing Your Dog: A Field Guide to Giving Your Canine Companion the Best Life Possible, A Dog’s World: Imagining the Lives of Dogs in a World Without Humans, Dogs Demystified: An A to Z Guide to All Things Canine, the second edition of The Emotional Lives of Animals, and Jane Goodall at 90: Celebrating an Astonishing Lifetime of Science, Advocacy, Humanitarianism, Hope, and Peace. (Many of his books can be seen here.) He also publishes regularly for Psychology Today. His homepage is marcbekoff.com. In 1986, Marc won the Master’s Tour du Haut, aka the age-graded Tour de France.

Follow Marc Bekoff at his Psychology Today blog and on Twitter.

See the full book list for Bark! Fest. We would love for you to support your local independent bookstore when getting the books.

For more information about Bark! Fest, subscribe to my newsletter. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Disclosure:

If you buy books linked to our site, we may earn a commission from

Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

[ad_2]