NANJING — A heartfelt obituary remembering “Laoma,” a deceased sun bear, has made national headlines in China.

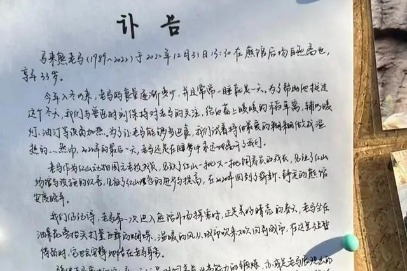

Published earlier this year in the Hongshan Forest Zoo in Nanjing, the capital of East China”s Jiangsu province, the obituary detailed the last days of the male bear’s 33-year life and the interactions between the animal and the keepers at the zoo.

“Since the beginning of winter in 2022, the bear’s food intake decreased, and he often slept for a whole day. In order to help him survive the winter, the keepers and the vets provided a warm straw nest for him and heated up his favorite vegetable mush,” reads the obit.

Guo Chenxu, the bear’s zookeeper, penned the obituary. His handwriting was neat and clear, an excellent match with his aspiration to treat animals with care and dignity.

“We still remember when ‘Laoma’ first entered the outer field of the bear house. It was a beautiful sunny spring. He sat next to the flowers and looked up at the butterflies. The warm wind blew from the city, quietly accompanying ‘Laoma,'” Guo wrote.

These sentimental words went viral on social media and were reposted by multiple Chinese news outlets, where people are used to reading zoo reports mostly about newborn animals and imports of exotic species.

In the past, the public rarely had a chance to see how zoos recorded and released the death information of their animals, especially the non-celebrity ones. They passed away invisibly and silently.

But now, Laoma is very much known to the world.

Guo hung the obit outside the bear house the day after Laoma died. The animal passed away while sleeping on Dec 31, 2022. Most sun bears have a life expectancy of around 20 years. Laoma reached 33, which is equivalent to 100 years of human life.

Writing an obituary has become a routine for Guo’s colleagues to express mourning for their deceased animal friends. In September 2020, the zoo wrote an obit for a river deer called “Zijin,” saying the animal had a friendly, calm and cooperative personality, and “always took the lead in eating when meals were served.”

Recounting the details of an animal’s life is a crucial comfort for the keepers to get through grief.

“We zookeepers are used to dealing with death, too,” said Peng Peila, the first one to write obits for the deceased animals at the zoo.

On the RIP notice for the deer, Peng wrote that Zijin will be missed but not forgotten. “We will always cherish the time we spent together.”

She observed the animal’s autopsy as the last message the animal left, so that zookeepers could learn how to provide better care for the breed’s surviving zoo family.

Like an organ donation from a car accident victim or the body of a patient given for cancer research, death sometimes has a silver lining. The same is true at the zoo.

“Although ‘Laoma’ has left us, we will take the attitude of life that the bear taught us, constantly improve ourselves with gratitude and take good care of every life,” the bear’s obit said.

In another widespread obituary released last October by Xining Wildlife Park in the northwestern province of Qinghai, the zookeepers paid tribute to a deceased Pallas’s cat: “Though neither enjoyed the wildlife nor breathed the air on the plateau, Sunsimiao (the cat’s name) has used its life to let we humans learn, understand and take care of the species.”

China’s only captive male Pallas’s cat, the deceased animal also provided an immortal monument in the study of the artificial breeding of this species, the zoo obit noted.

The memorial soon became the cause of an online discussion, with many netizens giving the thumbs up to the zoo, saying that the obit reflected how the keepers respected every life, while others questioned the zoo’s methods after learning the cat had died after choking on chicken while eating.

The park replied in a statement that it would review the incident and reassess the risks in its current breeding management.

But the media storm does not scare zookeepers. They continue to write memorials for their deceased friends. The latest death notice posted by the Hongshan Forest Zoo was for a bird, which was rescued from the wild by the zookeepers but died in February after being caged with other species. “This is a warning about the safety of mixing animals in small spaces. How to reduce the risk needs our more professional and continuous assessment and attention,” said the obit, which is still on display at the zoo.

Peng believes it is a keeper’s responsibility to inform visitors about the deaths of animals once kept within the zoo for exhibition.

Celebrity animals, such as pandas, koalas, and meerkats will draw more attention from tourists. But most of the non-star animals live in anonymity, without fans coming especially for them, Peng told media.

The death notices make people aware of the existence of more zoo animals.

Peng still remembered the scene two years ago when seeing some kids reading a boar’s obit word by word with the help of their parents at the zoo. Several months later, she was surprised, and certainly touched, to find a small white chrysanthemum attached to the obit.